cando miña nai morreu era moi novo,

e meu pai vendeume podendo a miña lingua

apenas berrar "sorralleiro! sorralleiro!"

así que limpo as vosas chemineas e durmo no sorrallo.

aí anda o pequeno Tom Dacre, que chorou cando a cabeza,

rizada coma costas de cordeiro, lle raparon: así que lle dixen

"cala, Tom!, non che importe, pois cando teñas a cabeza rapada

sabes que o sorrallo non che estragará eses cabelos brancos."

e así calou e esa mesma noite

cando durmía, tivo unha visión!

miles de sorralleiros, Dick, Joe, Ned e Jack

todos eles pechados en cadaleitos de negro.

e veu un Anxo cunha chave brillante,

e abriu os cadaleitos e liberounos;

brincan por unha planicie verde abaixo, rin, corren,

e lávanse nun río, e brilan ao Sol.

logo, espidos e brancos, cos sacos por aí,

suben ás nubes e xogan no vento;

e o Anxo díxolle a Tom, que se era un neno bo,

tería a Deus coma pai seu, e nunca lle faltaría ledicia.

e así espertou Tom; e erguémonos na noite,

e fomos traballar coas nosas bolsas e vasoiras.

inda que ía frío na mañá, Tom estaba ledo e non o sentía;

así que, se todos fan o seu traballo escusan temer mal.

|

| nenos da rúa na época na que apareceu o poema |

When my mother died I was very young,

And my Father sold me while yet my tongue

Could scarcely cry " 'weep! 'weep! 'weep! 'weep!"

So your chimneys I sweep, & in soot I sleep.

There's little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head,

That curl'd like a lamb's back, was shav'd: so I said

"Hush, Tom! never mind it, for when your head's bare

You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair."

And so he was quiet, & that very night

As Tom was a-sleeping, he had such a sight!

That thousands of sweepers, Dick, Joe, Ned, & Jack,

Were all of them lock'd up in coffins of black.

And by came an angel who had a bright key,

And he open'd the coffins & set them all free;

Then down a green plain leaping, laughing, they run,

And wash in a river, and shine in the Sun.

Then naked & white, all their bags left behind,

They rise upon clouds and sport in the wind;

And the Angel told Tom, if he'd be a good boy,

He'd have God for his father, & never want joy.

And so Tom awoke; and we rose in the dark,

And got with our bags & our brushes to work.

Tho' the morning was cold, Tom was happy & warm;

So if all do their duty they need not fear harm.

unha pequena cousa negra entre neve,

berrando "sorralleiro!" en clave de penar!

"onde están teu pai e túa nai? dime

"ambos subiron á igrexa a rezar."

"como estaba feliz sobre o páramo,

e sorría entre neve de inverno,

puxéronme roupa de morte

e ensináronme a cantar as notas de penar."

"e como son ledo e bailo e canto

pensan que non me fixeron mal

e foron cumprimentar Deus, o seu Crego e o Rei,

que da nosa miseria fan Ceo."

|

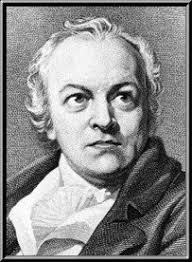

| William Blake |

A little black thing among the snow,

Crying " 'weep! 'weep!" in notes of woe!

"Where are thy father & mother? say?"

"They are both gone up to the church to pray."

"Because I was happy upon the heath,

And smil'd among the winter's snow,

They clothed me in the clothes of death,

And taught me to sing the notes of woe."

"And because I am happy and dance and sing,

They think they have done me no injury,

And are gone to praise God and his priest and king,

Who make up a heaven of our misery."

1. William Blake (1757-1827) publicou estes poemas (ambos chamados "The Chimney Sweeper") en 1789 (

Songs of Innocence) e 1794 (

Songs of Experience), respectivamente.

2. "sorralleiro" é unha variante dialectal empregada na provincia de Ourense, onde se preservan cousas xa desaparecidas noutras latitudes galegas. o termo sería "desenfeluxador." aquí non se utiliza porque en Cusanca falaban sempre do "sorrallo", non de "feluxe." ademais acábase antes.

3. os poemas fan referencia a un costume da época (socialmente aceptado) consistente na venda de nenos de catro ou cinco anos para limpar as chimineas. eran pequenos abondo para poder colarse polo oco abaixo e limpar o sorrallo que obturaba os condutos. nin que dicir ten que as súas condicións de traballo e vida eran absolutamente precarias.

4. a forma lírica empregada é o "couplet": pentámetros iámbicos con rima

aa bb ... esta tradución non consigue respectar este aspecto do orixinal.

5. en vista da temática claramente social destes dous poemas, chámame a atención que se describa a William Blake coma poeta "romántico" e agora teñamos un concepto tan deturpado do que significa ser tal cousa. xa sabedes, aquelo de "e que eu son moi romántic@." ou o romanticismo era outra cousa ou o deturpamos ata facelo inservible.

6. T. S. Eliot (1888-1965), outro grande, pero noutra póla totalmente distinta, describiu a arte de Blake coma "desacougante." estes dous poemas, cada un por si e os dous conxuntamnete, explican de xeito gráfico como hai momentos e lugares onde se alían a relixión, a clase política dominante, e a "sensatez" para consolidar feitos absolutamente crueis e inxustificados para algúns en beneficio doutros; neste caso, neniños pequenos limpando chimineas para que outr@s poidan estar ao quente no inverno. isto pasou, non foi conto. William Blake.

7. o canto da "experiencia" é explícito e acusatorio mentres que o da "inocencia" é implítico e irónico; por exemplo, a figura do Anxo poría en cuestión a relixión oficial, contribuínte neto á explotación de nenos crédulos en vez de protexelos e rescatalos da inxustiza.