|

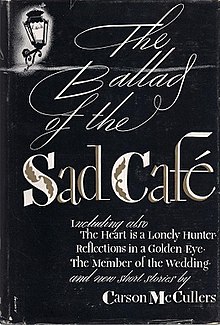

| die Verwandlung capa dunha das primeiras edicións 1916 |

Als Gregor Samsa

eines Morgens aus unruhigen Träumen erwachte, fand er sich in seinem Bett zu

einem ungeheueren Ungeziefer verwandelt. Er lag auf seinem panzerartig harten

Rücken und sah, wenn er den Kopf ein wenig hob, seinen gewölbten, braunen, von

bogenförmigen Versteifungen geteilten Bauch, auf dessen Höhe sich die

Bettdecke, zum gänzlichen Niedergleiten bereit, kaum noch erhalten konnte.

Seine vielen, im Vergleich zu seinem sonstigen Umfang kläglich dünnen Beine

flimmerten ihm hilflos vor den Augen.

»Was ist mit mir

geschehen?«, dachte er. Es war kein Traum. Sein Zimmer, ein richtiges, nur

etwas zu kleines Menschenzimmer, lag ruhig zwischen den vier wohlbekannten

Wänden. Über dem Tisch, auf dem eine auseinandergepackte Musterkollektion von

Tuchwaren ausgebreitet war - Samsa war Reisender - hing das Bild, das er vor

kurzem aus einer illustrierten Zeitschrift ausgeschnitten und in einem

hübschen, vergoldeten Rahmen untergebracht hatte. Es stellte eine Dame dar, die

mit einem Pelzhut und einer Pelzboa versehen, aufrecht dasaß und einen schweren

Pelzmuff, in dem ihr ganzer Unterarm verschwunden war, dem Beschauer

entgegenhob.

Gregors Blick

richtete sich dann zum Fenster, und das trübe Wetter - man hörte Regentropfen

auf das Fensterblech aufschlagen - machte ihn ganz melancholisch. »Wie wäre es,

wenn ich noch ein wenig weiterschliefe und alle Narrheiten vergäße«, dachte er,

aber das war gänzlich undurchführbar, denn er war gewöhnt, auf der rechten

Seite zu schlafen, konnte sich aber in seinem gegenwärtigen Zustand nicht in

diese Lage bringen. Mit welcher Kraft er sich auch auf die rechte Seite warf,

immer wieder schaukelte er in die Rückenlage zurück. Er versuchte es wohl

hundertmal, schloß die Augen, um die zappelnden Beine nicht sehen zu müssen,

und ließ erst ab, als er in der Seite einen noch nie gefühlten, leichten,

dumpfen Schmerz zu fühlen begann. »Ach Gott«, dachte er, »was für einen

anstrengenden Beruf habe ich gewählt! Tag aus, Tag ein auf der Reise. Die

geschäftlichen Aufregungen sind viel größer, als im eigentlichen Geschäft zu

Hause, und außerdem ist mir noch diese Plage des Reisens auferlegt, die Sorgen

um die Zuganschlüsse, das unregelmäßige, schlechte Essen, ein immer

wechselnder, nie andauernder, nie herzlich werdender menschlicher Verkehr. Der Teufel

soll das alles holen!« Er fühlte ein leichtes Jucken oben auf dem Bauch; schob

sich auf dem Rücken langsam näher zum Bettpfosten, um den Kopf besser heben zu

können; fand die juckende Stelle, die mit lauter kleinen weißen Pünktchen

besetzt war, die er nicht zu beurteilen verstand; und wollte mit einem Bein die

Stelle betasten, zog es aber gleich zurück, denn bei der Berührung umwehten ihn

Kälteschauer.

Er glitt wieder

in seine frühere Lage zurück. »Dies frühzeitige Aufstehen«, dachte er, »macht

einen ganz blödsinnig. Der Mensch muß seinen Schlaf haben. Andere Reisende

leben wie Haremsfrauen. Wenn ich zum Beispiel im Laufe des Vormittags ins

Gasthaus zurückgehe, um die erlangten Aufträge zu überschreiben, sitzen diese

Herren erst beim Frühstück. Das sollte ich bei meinem Chef versuchen; ich würde

auf der Stelle hinausfliegen. Wer weiß übrigens, ob das nicht sehr gut für mich

wäre. Wenn ich mich nicht wegen meiner Eltern zurückhielte, ich hätte längst

gekündigt, ich wäre vor den Chef hin getreten und hätte ihm meine Meinung von

Grund des Herzens aus gesagt. Vom Pult hätte er fallen müssen! Es ist auch eine

sonderbare Art, sich auf das Pult zu setzen und von der Höhe herab mit dem

Angestellten zu reden, der überdies wegen der Schwerhörigkeit des Chefs ganz nahe

herantreten muß. Nun, die Hoffnung ist noch nicht gänzlich aufgegeben; habe 2

ich einmal das Geld beisammen, um die Schuld der Eltern an ihn abzuzahlen - es

dürfte noch fünf bis sechs Jahre dauern -, mache ich die Sache unbedingt. Dann

wird der große Schnitt gemacht. Vorläufig allerdings muß ich aufstehen, denn

mein Zug fährt um fünf.«

|

| representación de Kafka escribindo publicada en 'Faro de Vigo' 07 de xaneiro de 2016 |

Und er sah zur

Weckuhr hinüber, die auf dem Kasten tickte. »Himmlischer Vater!«, dachte er. Es

war halb sieben Uhr, und die Zeiger gingen ruhig vorwärts, es war sogar halb

vorüber, es näherte sich schon dreiviertel. Sollte der Wecker nicht geläutet

haben? Man sah vom Bett aus, daß er auf vier Uhr richtig eingestellt war; gewiß

hatte er auch geläutet. Ja, aber war es möglich, dieses möbelerschütternde

Läuten ruhig zu verschlafen? Nun, ruhig hatte er ja nicht geschlafen, aber

wahrscheinlich desto fester. Was aber sollte er jetzt tun? Der nächste Zug ging

um sieben Uhr; um den einzuholen, hätte er sich unsinnig beeilen müssen, und

die Kollektion war noch nicht eingepackt, und er selbst fühlte sich durchaus

nicht besonders frisch und beweglich. Und selbst wenn er den Zug einholte, ein

Donnerwetter des Chefs war nicht zu vermeiden, denn der Geschäftsdiener hatte

beim Fünfuhrzug gewartet und die Meldung von seiner Versäumnis längst

erstattet. Es war eine Kreatur des Chefs, ohne Rückgrat und Verstand. Wie nun,

wenn er sich krank meldete? Das wäre aber äußerst peinlich und verdächtig, denn

Gregor war während seines fünfjährigen Dienstes noch nicht einmal krank

gewesen. Gewiß würde der Chef mit dem Krankenkassenarzt kommen, würde den

Eltern wegen des faulen Sohnes Vorwürfe machen und alle Einwände durch den

Hinweis auf den Krankenkassenarzt abschneiden, für den es ja überhaupt nur ganz

gesunde, aber arbeitsscheue Menschen gibt. Und hätte er übrigens in diesem

Falle so ganz unrecht? Gregor fühlte sich tatsächlich, abgesehen von einer nach

dem langen Schlaf wirklich überflüssigen Schläfrigkeit, ganz wohl und hatte

sogar einen besonders kräftigen Hunger.

die

Verwandlung

Franz

Kafka

unha

obra completada en 1912

traducido

ao galego por Xosé María García Álvarez e publicado como

A

metamorfose

Compostela,

Sotelo Blanco, 1990

Unha

mañá, ó espertar dun soño desacougante, Gregor Samsa achouse no seu leito

transformado nun insecto monstruoso. Estaba deitado sobre a dura coiraza do seu

lombo e, ó erguer un pouco a cabeza, percibiu a forma convexa e pardusca do seu

ventre dividido por longas e arqueadas costras, tan altas que o cobertor da

cama, que xa estaba a piques de esvarar ó chan, case nin se podía soster sobre

Blas. As súas numerosas patas, magoantemente fracas comparadas co grosor normal

das pernas de Gregor, buligaban desesperadamente perante os seus ollos.

«¿Que

me aconteceu?», pensou. Non, non era ningún soño. A súa habitación, aínda que

un pouco pequena, era un verdadeiro dormitorio humano e alí estaba, en calma,

no medio das lúas catro paredes, que para el eran ben familiares. Enriba da

mesa, sobre a que estaba estendido o contido dun mostrario de panos -Samsa era

viaxante- pendía a imaxe que había pouco el recortara dunha revista e encadrara

nun bonito marco dourado. Representaba unha dona cun chapeu de pel e un boá

tamén de pel; estaba sentada co busto dereito e sostendo fronte ó espectador un

enorme manguito de pel no interior do cal desaparecía todo o seu antebrazo.

|

| a metamorfose capa da edición galega 1990 |

Despois,

Gregor dirixiu a ollada á fiestra; o tempo grisallo -sentíanse cae-las pingas

de choiva sobre o beiril de lata da fiestra- meteulle no corpo unha grande

melancolía. «¿Como sería se durmise un pouco máis e esquecese todas aquelas

tolerías?», pensou. Pero ¡so era unha cousa completamente irrealizable, porque

estaba afeito a durmir sobre o costado dereito, pero no seu estado presente non

era quen de acadar esa postura. Por máis forza que empregaba en tombarse sobre

o seu lado dereito, sempre volvía, abaneándose, a quedar deitado sobre o lombo.

Tentouno polo menos cen veces; pechou os ollos para non ter que ve-lo buligar

das súas patas e só renunciou a seguir esforzándose cando comezou a sentir nun

costado unha dor lixeira, xorda, que aínda nunca experimentara. «¡Vállame

Deus!», pensou. «¡Que profesión tan esgotadora escollín! Nin un só día sen saír

de viaxe. Os sobresaltos profesionais son moito máis grandes ca na propia sede

central da empresa e, aínda por riba, impúxoseme esa praga de ter que andar de

viaxe, as preocupacións polos enlaces dos trens, a comida fóra de hora e de

mala calidade, unhas relacións humanas sempre cambiantes e curtas que nunca

chegan a ser cordiais. ¡Que o demo o leve todo!» Sentiu unha lixeira comechón

alá no alto da barriga. Vagarosamente, arrastrándose sobre as costas, foise

achegando ata un dos paus da cama para poder erguer mellor a cabeza. Atopou o

sitio onde lle picaba: estaba todo cuberto de puntiños brancos, que el non

conseguiu explicar. Quixo apalpa-lo sitio cunha pata, pero retirouna no mesmo

instante, porque só con tocalo ondas de calafrío lle percorrían o corpo.

Esvarou

ata a posición anterior. «Estes madrugóns», pensou, «apárvano a un totalmente.

O ser humano precisa do sono. Outros viaxantes levan unha vida de odaliscas.

Por poñer un caso, cando a media mañá volvo á fonda para anota-los pedidos,

eses señores aínda están sentados, a almorzaren. Se eu me atrevese a face-lo

mesmo co xefe que teño, botaríame fóra no intre. Por certo, ¿quen sabe se isto

ó mellor non é o que máis me convén? Se non me contivese, por mor de meus pais,

xa tiña pedida a baixa hai tempo; presentaríame diante do xefe e coa maior

franqueza diríalle o que penso. ¡Seguro que había caer do seu pupitre! Por

certo, que tamén é unha teima ben rara esa de sentar no pupitre e dende aquela

altura falarlle ó empregado, que, como o xefe é duro de oído, tense que achegar

mesmo a carón del. De calquera xeito, aínda non perdín toda a esperanza. En

canto teña xuntos os cartos para lle paga-la débeda de meus pais -aínda haberá

que agardar uns cinco ou seis anos-, vouno facer sen falta. E daquela

producirase a grande ruptura. Pero polo de agora téñome que erguer, porque o

meu tren sae ás cinco».

E

ergueu a vista cara ó espertador que seguía a face-lo seu tiquetaque sobre a

mesa de noite. «¡Deus divino!», dixo para os seus adentros. Eran as seis e

media, as agullas do reloxo seguían a avanzar tranquilamente, e mesmo xa pasaba

da media. E xa se achegaban ós tres cuartos. ¿Podería ser que, o espertador non

soase? Dende a cama víase ben que estaba correctamente posto para as catro da

mañá; certo que tivera que soar. ¿Pero sería posible seguir durmindo, coma se

nada, con aquel repenique que facía treme-los mobles? De feito, o que se di con

tranquilidade tampouco durmira, pero precisamente por iso tivera un sono máis

profundo. Pero, ¿que debería facer agora? O próximo tren tiña a saída ás sete;

para apañalo tería que bulir coma un tolo, pero o mostrario aínda estaba sen

empaquetar e el mesmo aínda non se sentía o que se di alá moi esperto e áxil.

E, mesmo se chegase a colle-lo tren, non podería esquivar unha pauliña do xefe,

porque o mozo do almacén estaría a esperar polo tren das cinco e xa iría un

anaco dende que dera parte da súa ausencia. Aquel rapaz era un monicreque do

xefe, servil e carente de entendemento. Mais, ¿que pasaría se mandase aviso de

que estaba enfermo? De calquera xeito, iso sería extraordinariamente magoante

para el e sospeitoso polo feito de que Gregor, nos seus cinco anos de servicio,

aínda non estivera enfermo nin unha soa vez. O máis probable era que viñese o

xefe acompañado polo médico do seguro: faríalles reproches a seus pais por

causa do lacazán de seu fillo e rexeitaría de raíz tódalas obxeccións coa

referencia do médico do seguro, para o cal só existen homes completamente sans,

pero preguiceiros. E, a propósito, ¿neste caso faltaríalle toda a razón? De

feito, á parte da sensación de somnolencia certamente inexplicable despois da

súa Tonga durmida, Gregor atopábase perfectamente ben e, o que aínda é máis,

estaba especialmente famento.